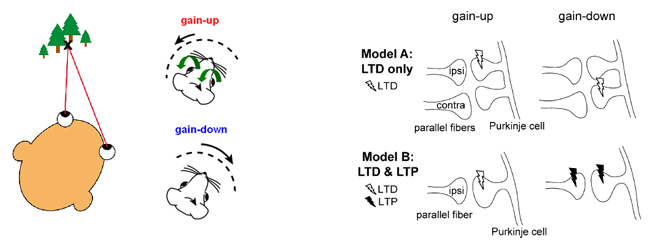

Learning systems must be able to store memories reliably, yet be able to modify them when new learning is required. At the mechanistic level, new learning may either reverse the cellular events mediating the storage of old memories or mask the old memories with additional cellular changes that preserve the old cellular events in a latent form. Behavioral evidence about whether reversal or masking occurs in a particular circuit can constrain the cellular mechanisms used to store memories. Here we examine these constraints for a simple cerebellum-dependent learning task, motor learning in the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR). Learning can change the amplitude of the VOR in two opposite directions. Contrary to previous models about memory encoding by the cerebellum, our results indicate that these behavioral changes are implemented by different plasticity mechanisms, which reverse each other with unequal efficacy.